I Promised to Protect My Source. Then Prosecutors Called.

A story of promises made, prosecutors on the march, and the boundaries of journalistic duty.

This article was originally written and edited in May 2009 to appear in The Washington Post’s now defunct Outlook section. I was The Post’s diplomatic correspondent at the time, and the piece was meant to explore the complex relationships between reporters and their sources in Washington. To my frustration, my article was never published. Over the years, I have provided the unpublished draft to journalism professors around the country to help generate classroom discussion. Steve Rosen died in 2024, and some of my recollections in this piece appeared in his Post obituary. Still, even more than 15 years later, I think my story would be of interest to the general public, which is why I am posting it on Substack.

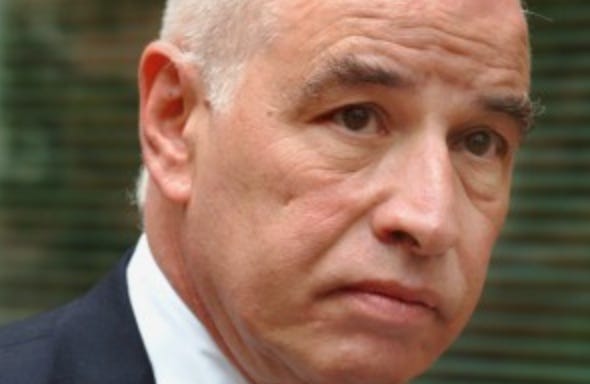

Steve Rosen of AIPAC

Last month [April 2009] I went to the federal courthouse in Alexandria and walked deep into the basement to enter a secure, windowless facility designed for holding classified information. I was there to listen to a conversation, recorded on a wiretap, that the government claimed was top-secret.

The person on one end of the line sounded familiar as his voice boomed out of the loudspeakers in that courthouse basement. It was me.

I was a potential defense witness in the case of United States v. Steven J. Rosen and Keith Weissman. They are two former lobbyists for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), whose case was dismissed earlier this month by a federal judge after the government withdrew charges that the two had broken a rarely used section of a 1917 law prohibiting the sharing of classified information.

My conversation with Rosen and Weissman, a brief ten-minute call on July 21, 2004 about Iranian actions in Iraq, was the key piece of evidence in the government's case. The two men were fired after the government played 11 seconds of that tape for AIPAC lawyers — and also reportedly threatened AIPAC with a potential indictment if they did not lose their jobs.

The AIPAC case struck at the heart of the information-trading that happens every day in this city and ultimately could have made it difficult to discover what the government was doing behind closed doors.

Rosen in particular had been a source of mine for more than three years, central to the reporting I do every day to inform readers of The Washington Post about the inner workings of the government. He would pick up information about U.S. policy toward Israel, as would I, and we would gossip, chat, discuss and puzzle over what we had learned. Rosen had unusually good sources in the U.S. government, and he directed me to information that often led to front-page stories.

As a lobbyist, Rosen had a particular point of view — a pro-Israel one. So I often would get off the phone with him and check what I had learned with other sources in the Palestinian community, the Arab diplomatic corps, and the Israeli and U.S. governments.

By balancing and vetting information from all these interest groups — each with their own perspective — I would come as close as possible to the truth.

Nevertheless, Rosen and Weissman were confidential sources, meaning I had made a promise not to reveal that they provided some of the information printed in the newspaper. But by the time I was asked to visit the Alexandria courthouse my sources were facing criminal prosecution. The government already knew every detail of my conversations with the lobbyists because it had placed a wire tap on Rosen's phones.

As I listened to our conversation, I knew I faced a dilemma: What is my obligation to a source in trouble?

This is not the first time I have faced this dilemma. Just a couple of months before I received that call from the AIPAC lobbyists, I testified in the grand jury proceeding involving vice presidential aide I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby about a conversation we had had on July 12, 2003. The vice president's chief of staff called me on my cellphone that day, interrupting an afternoon visit to the National Zoo with my children. The government wanted to know whether — while my young children scampered around the elephant house — Libby had revealed to me the identity of CIA operative Valerie Plame.

While several other reporters fought an ultimately losing battle to avoid testifying in the Libby case, I thought the answer was pretty clear cut. My source was in trouble, and I had information that I thought could help him.

I knew we had not discussed Plame. But I did not want to testify about the substance of our conversations. With the help of lawyers hired by The Washington Post, I reached an agreement with the prosecutor shielding me from all questions except whether Plame came up in our conversation.

Later, I was surprised to learn that Libby had told the grand jury that we had discussed Plame. He was indicted — and convicted on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice — for saying he had not discussed Plame with other reporters. But he testified to discussing Plame with me. In any case, my testimony at the trial — which suggested he had memory problems — did him little good.

Rosen and Weissman presented a different case. They were not government officials and had signed no documents saying they would keep the information they had learned confidential. They routinely met with government officials who told them nonpublic information, in part to get the word out to Jewish opinion leaders.

In this instance, Weissman had met with a Defense Department official named Lawrence A. Franklin, who told him an alarming story about Iranian activities in Iraq, including the possible targeting of Israeli agents. He convinced Weissman that the information was being ignored by more senior officials in the government and that the information was so urgent that he had to get it out fast.

Weissman immediately told Rosen, and then the two lobbyists called me and also spoke to a diplomat at the Israeli embassy. Little did they know that Franklin already had cut a deal with the prosecutors, who had been building a case against Rosen since at least 1999. The Pentagon staffer was working on their behalf, including, according to news accounts, wearing a wire during his conversation with Weissman.

While the government claimed the information the lobbyists gave me was so secret that I needed to listen to our conversation in a secure room behind double-locked doors, I never thought it was that earth shattering. Iran’s activities in Iraq were apparent to any reporter based in Baghdad at that time. Perhaps some official in Langley had stamped these details “secret” but I find it difficult to believe any national security issue was involved.

During the call, I pressed Weissman and Rosen about the quality of their information, and they would only say it came from “Virginia” — presumably code for the CIA or Pentagon. Weissman apologized for not telling me more, adding: “Just me telling you is probably some violation of the law.”

I laughed when he said that. The whole idea seemed ludicrous.

Rosen interjected: “It is not illegal to receive classified information.” He was right — and nearly four years after bringing the case the government implicitly conceded that by dropping all of the charges.

When Rosen and Weissman called me that day in 2004, they demanded confidentiality, as they usually did. And I promised it. For a journalist, maintaining that pledge is of the utmost importance. I will always maintain confidentiality if my source demands it. But there are no hard-and-fast rules when your source is in trouble — and your testimony could prove crucial to whether he or she ends up in jail.

I was prepared to testify in the case if necessary, assuming an agreement could be reached that I would not be questioned about conversations with other sources unconnected to the case. I believed there was nothing unique or unusual about the conversation I had with the two lobbyists. And none of these experiences have changed my dealings with confidential sources.

In the end, because I couldn't independently confirm the tip, I never wrote an article about what they told me. That is, until now.